/ Back / Home /

The Algorithm

The Quicksort algorithm is a sorting algorithm that uses the divide and conquer method. It has three main steps as follows:

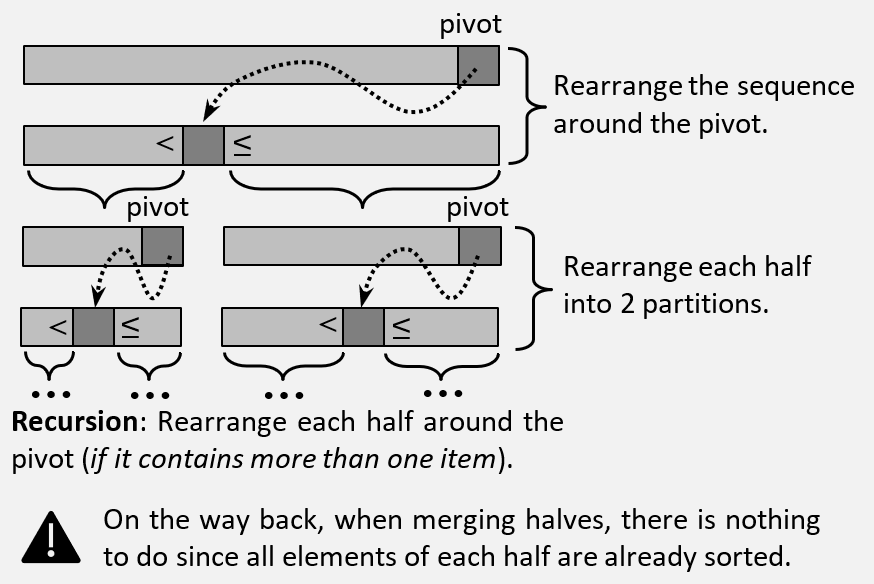

- Step 1: Divide: the given sequence is arranged around a chosen pivot, thus resulting in two partitions, the elements greater than or equal to the pivot in one part and the remaining elements in the other;

- Step 2: Conquer: each partition is sorted recursively by Quicksort;

- Step 3: Combine: since the two partitions are already sorted, there is nothing to do at this step.

Description

Like Merge-sort, Quicksort can be implemented recursively or iteratively using a stack. Both implementations can be found below. The iterative version has some advantages, for example, in practice it is somewhat faster, and stack-overflow can be avoided or controlled more easily, but for the sake of simplicity, I will consider the recursive version, since it is easier to understand and simpler to implement.

The most important step in this algorithm is partition. In this step, an element called the pivot is chosen, around which the sequence is rearranged so that the elements greater than or equal to the pivot are to the right of it and the rest to the left. Then recursively partition the left side and the right side. The base case is when a partition contains at most 1 element. One more thing must be specified, namely the pivot can be any element in the sequence, so if it is chosen randomly (using a uniform distribution) the algorithm can guarantee a time complexity of \(nlog_n\) (i.e. Randomized Quicksort).

See below the graphical representation of qsort:

Important Note: The main difference between Merge-sort and Quicksort consists in the fact that the former does most of the work at merge step (i.e. recursive merging), while the latter does most of the work at divide step (i.e. recursive partitioning). And, even though both algorithms have the same asymptotic complexity, in practice Quicksort outperforms Merge sort, mostly because it has better constants and it uses less space.

Implementation

Recursive version

void quicksort(vector<int>& a) {

if (a.size() <= 1) return;

qsort(a, 0, a.size()-1);

}

void qsort(vector<int>& a, int s, int e) {

if (e <= s) return;

int p = partition(a, s, e);

qsort(a, s, p - 1);

qsort(a, p + 1, e);

}

int partition(vector<int>& a, int s, int e) {

/**

* a[s] is the pivot

* For Randomized QuickSort, chose a random pivot between s and e and

* swap it with a[s]; the partitioning remains as is.

*/

int p = s + rand() % (e - s + 1);

swap(a[s], a[p]);

int i = s;

for (int j = s + 1; j <= e; j++) {

if (a[j] < a[s]) swap (a[++i], a[j]);

}

swap (a[s], a[i]);

return i;

}

Iterative version

void sort(vector<int>& a) {

if (a.size() <= 1) return;

stack<pair<int, int>> st;

st.push(make_pair(0, a.size()));

// preorder traversal of indexes

while (!st.empty()) {

pair<int, int> n = st.top(); st.pop();

int s = n.first, e = n.second;

int p = partition(a, s, e);

if (e - (p + 1) > 1) st.push(make_pair(p + 1, e));

if (p - s > 1) st.push(make_pair(s, p));

}

}

Correctness

The correctness of Quicksort can be proven by induction, but I want to stay away from the complexity of the mathematics, since this rigorous proof can be found in various books. So, at the beginning, the initial sequence is partitioned around a chosen pivot. After the first partitioning, we know that all elements smaller than this pivot will be on the left side and those larger or equal on the right side. For these halves to be sorted, we apply the same method again for each of them. It is obvious that keep halving, at some point the parts will contain at most one element. In this case, the pivot will have at most 1 element smaller than it on the left side and at most 1 element bigger on the right side, so we have a sorted sub-sequence. Let’s consider that both sub-sequences are sorted applying the same principle. Thus, looking at the previous step, we have the 2 sequences sorted to the left and to the right of the pivot, so the entire sequence is sorted. Keep applying this principle up to the initial sequence, it is obvious that it will be sorted.

Complexity Analysis

Time Complexity

In the worst-case scenario, at each recursion step the items are rearranged into one partition of size \(n-1\) and one of size \(0\) (a partition with no items), hence the running-time can be expressed as follows:

\(T(n) = T(n-1) + T(0)+T_Partition(n)\) , where \(T_Partition(n) = Θ(n)\). \(T(n) = T(n-1) + \Theta(n) = cn + c(n-1) + c(n-2) + ... + c = \sum_{k=0}^{n}cn = cn^2 = \Theta(n^2)\).

This can be proved by using “Guess-and-Confirm” method that the inequality holds for \(c \geq 1\) and \(n \geq 1\).

The calculation of running-time complexity in the average-case requires some knowledge about probabilities and random variables (see CLRS, section 7.4 or the Professor Charles E. Leiserson’s course - public MIT Open Courseware). Although this is rather hard to prove, we can see using the recursive tree that if at each recursive step the elements are rearranged into two partitions, one containing 10% of the elements and the other 90% of them the complexity is \(T(n) = O (nlog_2n )\). So, we can say that the algorithm is closer to the average case than the worst case. This statement is a very strong one because it makes quicksort a better choice than mergesort because the worst case is very unlikely to occur, to which is added a much better space complexity plus smaller constants.

Best-case is similar with average case. In base case each time the pivot lands exactly in the middle of the sequence, so obviously \(T(n) = O(nlog_2n)\).

Space Complexity (auxiliary)

The (auxiliary) space complexity is \(O(1)\) if we do not consider the stack frames, and with them it is \(O(n)\) in the worst case.

Stability

Quicksort is not a stable algorithm. Let’s consider the following sequence of numbers: 5, 2, 2’, 6. We choose 5 as the pivot. Thus, after partitioning the sequence around 5 (using the code above), results: 5, 2, 2’, 6 => switch(5, 2’) => 2’, 2, 5, 6. As can be seen 2 and 2’ have been reversed.

Note: I suggest to run it on paper :).

/ Back / Home /