The Problem

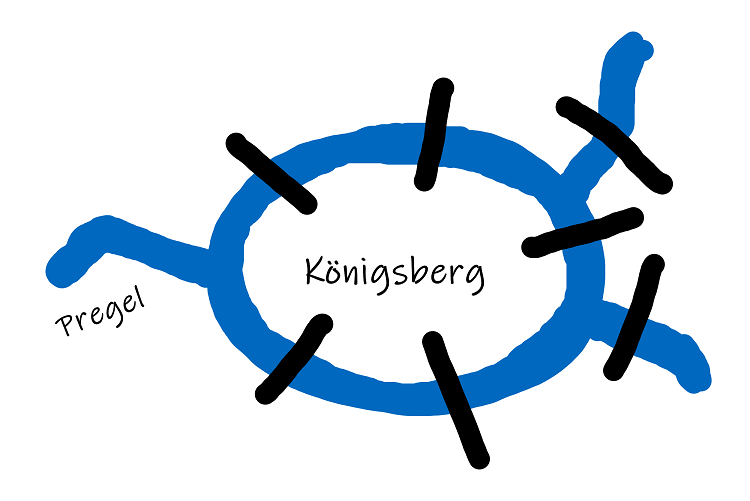

The citizens of Königsberg (now known as Kaliningrad) dislikes to retrace their steps when taking a walk. So, they wanted to determine a route across the bridges over the Pregel (now Pregolya) river that starts from a point and return by crossing each bridge exactly once.

There were many attempts, but the first solution was found by Leonhard Euler in 1736, hence the name Eulerian Circuit.

The Approach and The Proof Sketch

Theorem 1: A graph \(G\) contains an Eulerian Circuit iff \(G\) is connected and each node has even degree.

Note: This theorem can be extended to digraphs as well so, in this case the even degree transforms into \(indegree(v) = outdegree(v)\).

Let’s assume that whenever we traverse an edge, that edge disappear. So, intuition tells us that if we leave a node we need to go back and close that path, hence form a cycle. To do so, each node must have even degree, otherwise there is no way we can go back to that node and close the path.

The Eulerian Cycle is found by partitioning the edge set of \(G\) it into cycles and then nest all of them into a complete cycle. There are several algorithms that have different approaches, but all of them are based on this property: Fleury’s, Hierholzer’s and Tucker’s algorithm. I will handle only the first two.

Theorem 2: If the edge set of \(G\) can be partitioned into cycles, then graph \(G\) contains an Eulerian Cycle.

Induction hypothesis: assume that for any \(1 \leq k \leq m\) cycles, there is a circuit that contains only the edges of those \(k\) cycles and no other edge of \(G\).

Base case: the hypothesis holds for \(k = 1\).

Inductive step: assume there a cycle \(C\) that contains the edges of only the \(k < m\) cycles and no other edge of \(G\). Since \(G\) is connected then at least one node of \(C\) is contained by other cycles. Let \(C_1\) be that cycle and \(v\) be the common node. Then start from \(v\) and traverse \(C_1\) and then follow \(C\). Clearly \(C_1\) contains the edges of \(k+1\) cycles and no other edge, hence the hypothesis holds.

Note: We can use the first theorem to see if \(G\) contains a Eulerian Cycle, because it is easy and fast (i.e. \(O(V)\) using proper structures) and the second one to actually find the cycle.

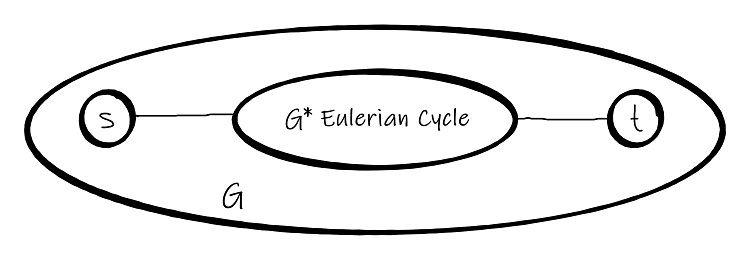

There is also the notion of Eulerian Path. In this case there are only \(2\) nodes of odd degree (the start and the end points) and the rest of them must be of even degree. Basically, an Eulerian Cycle with 1 entry and 1 exist.

Hierholzer’s algorithm

Construct the Eulerian Cycle by connecting pair-wise disjunctive cycles. Basically, we apply iteratively the second theorem. We start with an arbitrary node and follow an arbitrary unvisited edge to its neighbours. We continue this way until we return to the starting node, thus completing a cycle. Then, choose an arbitrary node from this cycle that has an unvisited edge and again, follow a path of unvisited edges until we return to this original node. Now, merge the two cycles by replacing the common node in the first cycle with the second cycle, thus we obtain a circuit. Continue this way until all the cycles are discovered and merged. The result is the Eulerian Cycle.

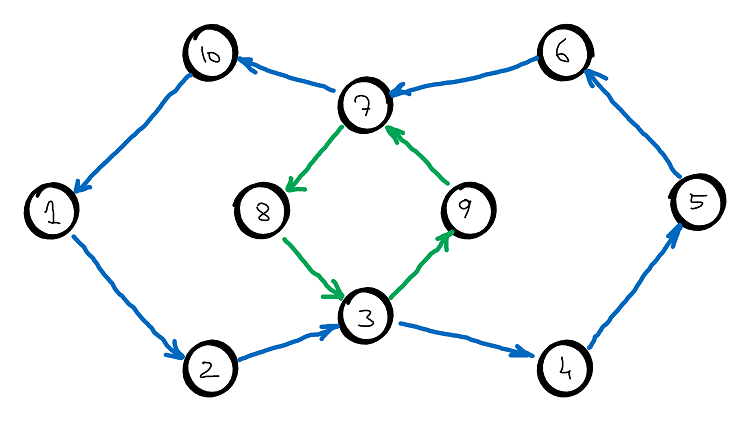

Example

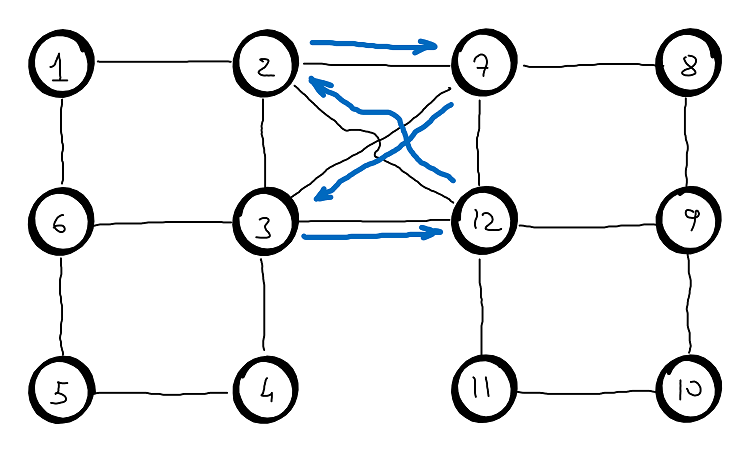

First cycle: \(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10, 1\)

Second cycle:

\(3, 9, 7, 8, 3\) if we choose the common node \(3\)

\(7, 8, 3, 9, 7\) if we choose the common node \(7\)

Merge cycles and obtain the Eulerian Cycle:

\(1, 2, 3, 9, 7, 8, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10, 1\) for common node \(3\)

\(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 3, 9, 7, 10, 1\) for common node \(7\)

Implementation

In the previous example we can observe that if we choose node \(7\) as starting node for the second cycle (i.e. node \(7\) being common to both cycles), then all nodes that comes after it are completed (i.e. no unvisited edge). In other words is just the DFS reverse postorder.

pair<bool, vector<int>>

hierholzer(int n, vector<vector<int>>& adjL) {

vector<int> cycle;

// check in-degree(v) == out-degree(v)

if (!hasEulerian(n, adjL))

return make_pair(false, cycle);

// eulerian cycle

vector<vector<bool>> marked(n, vector<bool>(n, false));

preorder(0, n, adjL, cycle, marked);

return make_pair(true, cycle);

}

void preorder(int u, int n, vector<vector<int>>& adjL, vector<int>& cycle, vector<vector<bool>>& marked) {

for (int v : adjL[u]) {

if (marked[u][v] == true) continue;

// mark the edge

marked[u][v] = true;

marked[v][u] = true;

preorder(v, n, adjL, cycle, marked);

}

cycle.push_back(u);

}

bool hasEulerian(int n, vector<vector<int>>& adjL) {

vector<int> in(n, 0), out(n, 0);

for (int u = 0; u < n; u++) {

for (int v : adjL[u]) {

out[u]++; in[v]++;

}

}

for (int u = 0; u < n; u++)

if (in[u] != out[u]) return false;

return true;

}

Fleury’s algorithm

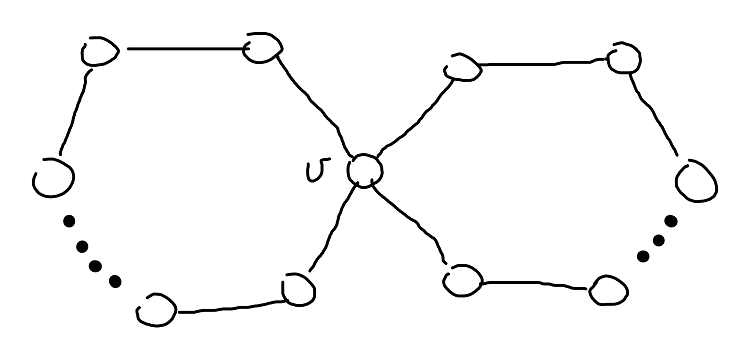

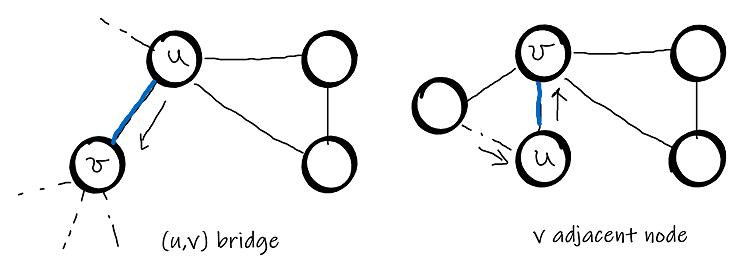

Felury’s approach is more similarly of how a human would draw this cycle. Basically, how to draw a cycle through a graph without drawing the same edge twice and with continuous stroke. Start with an arbitrary node, constantly expanding the number of edges be used in the trail, while avoiding bridges. A bridge is used when no other choice is available.

A bridge is an edge that disconnects the graph into connected components. We avoid bridges, because when a bridge is crossed we end up with two disconnected components, and then there is no path back to one of the components (see the example below).

Let’s assume we start from node \(2\) and we follow this path \(2 \rightarrow 7 \rightarrow 3 \rightarrow 12 \rightarrow 2\). Obliviously, by doing this we end up with 2 connected components and there is no way to go back and traverse the edges from the right component.

We say that an edge \((u,v)\) is safe iff:

– it is not a bridge

– \(v\) is the only adjacent node

Algorithm steps:

- Choose an arbitrary node

- chose a safe edge

- label the edge in the order you travel

- when there is no more edges to cross, stop.

Implementation

pair<bool, vector<int>>

fleury(int n, vector<vector<int>>& adjL) {

vector<int> cycle;

// check in-degree(v) == out-degree(v)

if (!hasEulerian(n, adjL))

return make_pair(false, cycle);

vector<vector<bool>> markedEdges(n, vector<bool>(n, false));

fluery(0, n, adjL, markedEdges, cycle);

return make_pair(true, cycle);

}

void fluery(int u, int n, vector<vector<int>>& adjL, vector<vector<bool>>& markedEdges, vector<int>& cycle) {

bool last_first = true;

for (int v: adjL[u]) {

if (markedEdges[u][v] == true) continue;

last_first = false;

// is edge(u,v) safe (not bridge, or the only incident edge to u)?

if (safe(u, v, n, adjL, markedEdges) == true) {

markedEdges[u][v] = true;

markedEdges[v][u] = true;

cycle.push_back(u);

fluery(v, n, adjL, markedEdges, cycle);

}

}

// when we reach at starting vertex, then there is no incident edge, so

// just add it to the cycle;

if (last_first == true) cycle.push_back(u);

}

bool safe(int u, int v, int n, vector<vector<int>>& adjL, vector<vector<bool>>& markedEdges) {

// is (u,v) the only incident edge to u ?

int adjc = 0;;

for (int v: adjL[u]) {

if (markedEdges[u][v] == true) continue;

adjc++;

}

if (adjc == 1) return true;

// is (u,v) a bridge ?

markedEdges[u][v] = true;

markedEdges[v][u] = true;

int cu = reachable(u, n, adjL, markedEdges); // # of vertices reacheable from u

int cv = reachable(v, n, adjL, markedEdges); // # of vertices reacheable from v

markedEdges[u][v] = false;

markedEdges[v][u] = false;

return (cu == cv);

}

int reachable(int start, int n, vector<vector<int>>& adjL, vector<vector<bool>>& markedEdges) {

vector<bool> marked(n, false);

int cnt = 0;

reachable(start, adjL, marked, markedEdges, cnt);

return cnt;

}

void reachable(int u, vector<vector<int>>& adjL, vector<bool>& marked, vector<vector<bool>>& markedEdges, int &cnt) {

marked[u] = true;

cnt++;

for (int v : adjL[u]) {

if (marked[v] == true) continue;

if (markedEdges[u][v] == true) continue; // edge already in circuit

reachable(v, adjL, marked, markedEdges, cnt);

}

}