- What is an algorithm?

- What analysis of algorithms means?

- Basic concepts of efficiency analysis

- The basics of asymptotic analysis

- Divide-and-conquer recurrences

- Probabilistic Analysis and Randomized Algorithms

- Amortized Analysis

/ Back / Home /

What is an algorithm?

An algorithm is a method of solving a problem step by step. In essence, it describes the steps necessary to process the input data to obtain the output data (i.e. the solution of the problem). Just and FYI: the term algorithm was given by the Persian astronomer, mathematician, and writer Abu Abdullah Muhammad bin Musa al-Khwarizmi in the 9th century.

An algorithm must have the following properties:

- Generality: the algorithm must generate the solution to the problem for any input data, not only for particular values

- Termination: the algorithm should always stop after a finite number of steps

- Deterministic: each step of the algorithm must be described without ambiguity

- Correctness: the algorithm is correct if it allows obtaining the solution starting from the initial input data.

- Efficiency: the efficiency of the algorithm is given by the amount of resources used: space (for the data) and time (for the execution).

What analysis of algorithms means?

The analysis of algorithms include the analysis of the properties stated above, especially the analysis of correctness and that of efficiency, the others being most often included in the correctness analysis. The analysis can be done in 2 ways: experimental and analytical. The experimental variant is obviously the simplest, but it has the disadvantage that it does not cover the entire range of input data and most of the time it is not possible to draw a general conclusion regarding the correctness of the algorithm. So, we are mostly interested in the analytical analysis because it is the one that proves the correctness of the algorithm without a trace of doubt, the disadvantage is that it is difficult to find such a proof.

The following three main steps are required for analytical analysis:

- Identification of input data properties (pre-conditions)

- Identification of output data properties (post-conditions)

- Proof that, starting from the input data and applying the steps described by the algorithm, the post-conditions are met.

For example, let’s consider a sorting algorithm. Let’s assume that this algorithm sorts arrays containing only natural numbers smaller than \(10^5\). So, the pre-conditions are: the array can be empty or contain natural numbers between \(1\) and \(10^5\). The post-condition is that this array is sorted, so for any \(2\) consecutive numbers \(a[i], a[i+1], a[i] \leq a[i+1]\). If it is formally proved that starting from the input data satisfying these pre-conditions, is obtained the output data satisfying the post-condition above, the algorithm is correct.

The analytical analysis of the efficiency, known as the space and time complexity, aims to estimate the volume of resources required for the execution of the algorithm. This analysis is useful to determine if an algorithm consumes a reasonable amount of resources, otherwise, even if the algorithm is correct, it is not considered efficient and most of the time it cannot be used in practice. Also, the analysis is done regardless of the characteristics of the machine or the programming language used and thus allows the comparison of several correct algorithms for solving the same problems. In general, the amount of resources required depends on the size of the input data. In fact, we are interested in how resource consumption varies with input size, so we are interested in the asymptotic analysis of this variation. For example, if we know that the resources consumed by an algorithm grow exponentially with the size of the input data and another algorithm consumes linearly, then the second one is obviously more efficient.

Now, lets see a simple example of an analytical analysis of an algorithm.

Given an array \(a\) of \(n\) distinct positive numbers and a value \(x\), we want to build a simple algorithm that search \(x\) in array and return its position or \(-1\) if not found.

| The search algorithm | Cost/line | Times

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

| 01. int find(vector<int>& a, int x) { | |

| 02. int idx = -1; | c1 | 1

| 03. for (int i = 0; i < a.size(); i++) { | c2 | k <= n

| 04. if (a[i] == x) { | c3 | k <= n

| 05. idx = i; | c4 | 1

| 06. break; | c5 | 1

| 07. } | |

| 08. } | |

| 09. | |

| 10. return idx; | c6 | 1

| 11.} | |

In the second column you can find the execution costs of each line of code and in the third column, you can find the number of executions of each line until \(x\) is found or until the entire array is exhausted.

Let’s denote by \(T(n)\) the execution time of this algorithm, where \(n\) is, obviously, the number of elements in the array. So, \(T(n)\) is built this way:

\(T(n) = c_1 + kc_2 + kc_3 + c_4 + c5 + c6 \text { ,where } c_i \text{ is the cost of running line i and k is the number of times line i is executed }\).

\(T(n) = k(c_1 + c_2) + c_1 + c_4 + c_5 + c_6 \text{ ,where } k \le n\).

\(T(n) = ak + b \text{ ,where } a = c_2 + c_3 \text{ and } b = c_1 + c_4 + c_5 + c_6\).

In the worst-case scenario \(k = n\), which means that \(T(n) = an + b\). Looking at the terms of the function \(T(n)\), it is obvious that the term \(an\) matters most to the value of \(T(n)\). Actually, at the limit, when \(n\) is very large, the constants \(a\) and \(b\) matter very little to nothing. So, we can say that our algorithm varies linearly with the size of the array and we can denote \(T(n) = O(n)\) - the asymptotic notation.

In the best-case scenario \(k = 1\), thus \(T(n) = a + b\). So, the execution time is constant regardless of how big is the input size.

There is also the average-case scenario. Usually, this involves some probabilitic analysis, but for this particular example it is easy to see that \(T(n) = a\frac{n}{2} + b\) and the execution time is the same as for the worst-case scenario: \(T(n) = O(n)\).

That was the efficiency analysis, but what about correctness? Is the algorithm correct for any input and not only for some particular input ?

Of course it is, you can tell just by eyeballing at it, but for most algorithms it’s not that obvious and it’s quite hard to prove.

You can see code line 03 where all the values in the array are iterated. Each value is tested against the searched value \(x\) and no value from the array is omitted. This can be seen at code line 04. If the value of \(x\) is found, the position of it is saved in the \(idx\) variable and then the iteration is interrupted and this \(idx\) value is returned to the caller. This can be seen at code lines 05, 06 and 10. If the value of \(x\) is not found, then the value \(-1\) remains set in \(idx\) and this value is now returned to the caller. Thus, the algorithm is correct if the values in the array are distinct and are between \(1\) and \(10^5\).

Basic concepts of efficiency analysis

So, as I mention before, the algorithms analysis refers to the assessment of the necessary resources to execute the algorithms: running time and space usage. The running time is the number of steps executed by an algorithm and the time complexity is a theoretical estimation of the increase of running time of an algorithm as its input size increases. Similar, the space complexity is a theoretical estimation of the increase of the amount of space used by an algorithm as its input size increases.

In general, the time or space is represented as a function of the input size (as you see in the example above). The limiting behavior of these functions reflects the behavior of the algorithm for very large inputs, this being the main target, while the behavior for small input sizes is usually ignored. Though, the small input sizes are relevant mostly for real time applications. For the analysis of limiting behavior is used a mathematical method called asymptotic analysis, who gives, in this case, an estimation of the complexity for a given resource (i.e. asymptotic bounds).

The behavior of an algorithm is analyzed in three different conditions:

- In worst conditions (worst-case): aims to define an upper bound of resources usage (at most);

- On average (average-case): aims to define the average amount of resources usage over all possible input instances;

- In optimal conditions (best-case): aims to define a lower bound of resources usage (at least).

In other words, in the worst-case scenario, the bounds define the maximal amount of resources used when the input size grows indefinitely. Similarly, the bounds in the best and average cases define the minimum and average amount of resources used. Most often, worst and average cases are analyzed because these cases are most desired to be improved.

In the average-case scenario, the analysis gives an estimation of the average complexity. From mathematical point of view, considering the sample space of all inputs of a size \(n\) and fix a probability distribution (usually, chosen to be a uniform distribution, which means that every input of size \(n\) has the same probability to occur), the analysis reduces to the computation of the expected value of a random variable defined on this sample space. As an example, see the asymptotic analysis of Quicksort. This method is called probabilistic analysis and it is quite complicated because it requires consistent knowledge about probabilities and random variables.

Finally, in case an algorithm involves a series of operations, where just some of them are very costly while the majority are of low cost, worst-case scenario might be too pessimistic. Hence, the amortized analysis gives a more relevant view of the algorithm efficiency. This analysis is most suited when operations are invoked frequently, and it guarantees the average performance of every operation in a sequence in the worst-case scenario.

The basics of asymptotic analysis

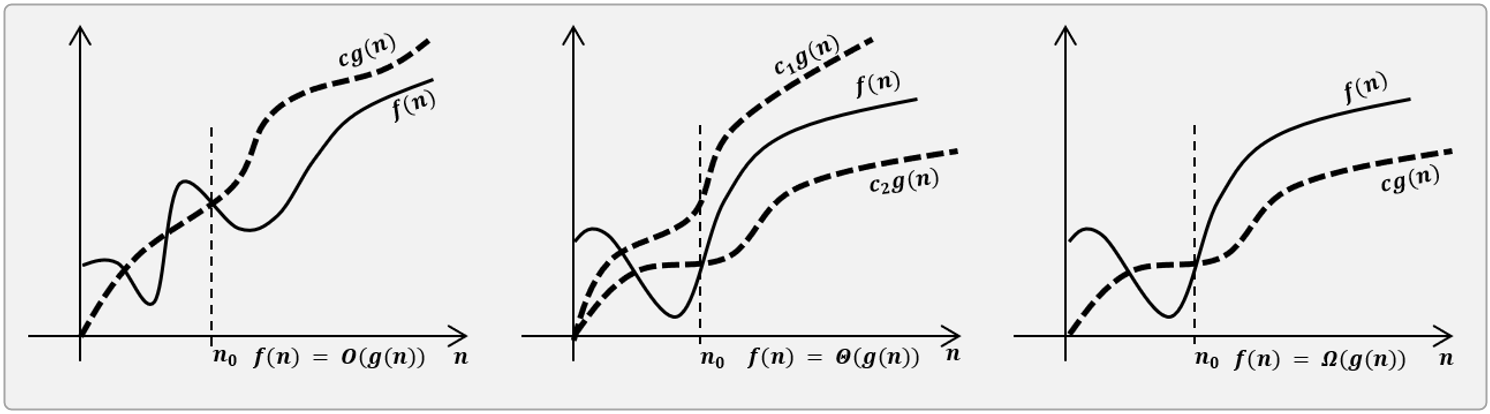

The asymptotic analysis is a method of analyzing the behavior of functions when they approach boundaries. Given a function \(f(n)\), three asymptotic bounds are defined:

-

Asymptotic upper bound, “big-Oh of g of n” written as \(f(g(n)) = O(g(n))\): \(O(g(n)) = \left \{ f: N \rightarrow R_+ \text{ }\vdots\text{ } \exists c \in R_+, c > 0, \exists n_0 \in N_+ \text{ such that } 0 \leq f(n) \leq c\cdot g(n) \text{ for all } n > n_0 \right \}\).

-

Asymptotic tight bound, “big-Theta of g of n” written as \(f(g(n)) = \Theta(g(n))\): \(\Theta (g(n)) = \left \{ f: N \rightarrow R_+ \text{ }\vdots\text{ } \exists c_1, c_2 \in R_+, c_1,c_2 > 0, \exists n_0 \in N_+ \text{ such that } 0 \leq c_1 \cdot g(n) \leq f(n) \leq c_2 \cdot g(n) \text{ for all } n > n_0 \right \}\).

-

Asymptotic lower bound, ”big-Omega of g of n” written as \(f(n) = \Omega(g(n))\): \(\Omega(g(n)) = \left \{ f: N \rightarrow R_+ \text{ }\vdots\text{ } \exists c \in R_+, c > 0, \exists n_0 \in N_+ \text{ such that } 0 \leq c\cdot g(n) \leq f(n) \text{ for all } n > n_0 \right \}\).

The definitions above indicate that \(O, \Theta\), and \(\Omega\) define sets of functions, thus the statement \(f(n) = O(g(n))\), means that \(f(n)\) is a member of the set defined by \(O(g(n))\). Similar for the other two bounds \(\Theta\) and \(\Omega\).

The tight bound definition points that \(g(n)\) is both lower and upper bound, thus an immediate property emerges: a function \(f(n) = \Theta(g(n))\) if and only if \(f(n) = O(g(n))\) and \(f(n) = \Omega(g(n))\).

Note: This property can be used to prove that a bound is asymptotically tight when upper and lower bounds are known or easier to prove.

The definitions of Big-Oh and Big-Ω indicate that the inequalities hold for some constant. If the inequalities hold for all constants, then the following bounds (named little-oh and little-ω) are defined formally as follows:

-

Asymptotically smaller, “little-oh of g of n” written a \(f(n) = o(g(n))\). \(o(g(n)) = \left \{ f: N \rightarrow R_+ \text{ }\vdots\text{ } \forall c \in R_+, c > 0, \exists n_0 \in N_+ \text{ such that } 0 \leq f(n) \leq c\cdot g(n) \text{ for all } n > n_0 \right \}\).

-

Asymptotically larger, ”little-omega of g of n ” written as \(f(n) = \omega(g(n))\) \(\omega(g(n)) = \left \{ f: N \rightarrow R_+ \text{ }\vdots\text{ } \forall c \in R_+, c > 0, \exists n_0 \in N_+ \text{ such that } 0 \leq c\cdot g(n) \leq f(n) \text{ for all } n > n_0 \right \}\)

Hence, additional important properties emerge:

- the functions that are in \(O\) but not in \(\Theta\) are in little-oh: if \(f(n) = o(g(n))\) then \(f(n) = O(g(n))\) and \(f(n) \neq \Theta(g(n))\).

- the functions that are in \(\Omega\) but not in \(\Theta\) are in little-omega: if \(f(n) = \omega(g(n))\) then \(f(n) = \Omega(g(n))\) and \(f(n) \neq \Theta(g(n))\).

Note: If the following limits exist and the functions \(f\) and \(g\) are positive functions, then the asymptotic bounds can be defined based on limits as follows:

- if \(f(n) = O(g(n))\), then \(\frac{f(n)}{g(n)}\overset{n \rightarrow \infty}{\rightarrow} c\) (where \(0 \le c < \infty\)) : \(f\) and \(g\) grows at the same rate;

- if \(f(n) = O(g(n))\), then \(\frac{f(n)}{g(n)}\overset{n \rightarrow \infty}{\rightarrow} 0\) : \(f\) grow more slowly than \(g\);

- if \(f(n) = O(g(n))\), then \(\frac{g(n)}{f(n)}\overset{n \rightarrow \infty}{\rightarrow} c\) (where \(0 < c \le \infty\)): first case mirrored.

- if \(f(n) = O(g(n))\), then \(\frac{g(n)}{f(n)}\overset{n \rightarrow \infty}{\rightarrow} 0\) : \(f\) grow more slowly than \(g\);

- if \(f(n) = \Theta(g(n))\), then \(\frac{f(n)}{g(n)}\overset{n \rightarrow \infty}{\rightarrow} c\) (where \(0 < c < \infty\)) : the two functions grow at the same rate and the difference between them is insignificant.

Arithmetic of the asymptotic bounds

- Summing:

- if \(f_{1}(n) = O(g_{1}(n))\) and \(f_{2} = O(g_{2}(n))\) then \((f_{1} + f_{2})(n) = O(max(g_{1}(n), g_{2}(n)))\).

- if \(f_{1}(n) = \Theta(g_{1}(n))\) and \(f_{2} = \Theta(g_{2}(n))\) then \((f_{1} + f_{2})(n) = \Theta(max(g_{1}(n), g_{2}(n)))\).

- if \(f_{1}(n) = \Omega(g_{1}(n))\) and \(f_{2} = \Omega(g_{2}(n))\) then \((f_{1} + f_{2})(n) = \Omega(max(g_{1}(n), g_{2}(n)))\).

- Scaling:

- if \(f(n) = O(g(n))\) then for \(\forall k > 0, f(n) = O(kg(n))\).

- if \(f(n) = \Theta(g(n))\) then for \(\forall k > 0, f(n) = \Theta(kg(n))\).

- if \(f(n) = \Omega(g(n))\) then for \(\forall k > 0, f(n) = \Omega(kg(n))\).

- Transitivity:

- if \(f(n) = O(g(n))\) and \(g(n) = O(h(n)) \overset{implies}{\rightarrow} f(n) = O(h(n))\).

- if \(f(n) = \Theta(g(n))\) and \(g(n) = \Theta(h(n)) \overset{implies}{\rightarrow} f(n) = \Theta(h(n))\).

- if \(f(n) = \Omega(g(n))\) and \(g(n) = \Omega(h(n)) \overset{implies}{\rightarrow} f(n) = \Omega(h(n))\).

- Reflexivity:

- \(f(n) = O(f(n))\).

- \(f(n) = \Theta(f(n))\).

- \(f(n) = \Omega(f(n))\).

- Symmetry:

- \(f(n) = \Theta(g(n))\) if and only if \(g(n) = \Theta(f(n))\).

- Transpose symmetry:

- \(f(n) = O(g(n))\) if and only if \(g(n) = \Omega(f(n))\).

- \(f(n) = o(g(n))\) if and only if \(g(n) = \omega(f(n))\).

- Order of growth: Only the dominant terms become relevant because the lower order terms are relatively insignificant for very large values of \(n\).

Common Rates of Growth

- Constant: \(\Theta(c)\)

- Linear: \(\Theta(n)\)

- Logarithmic: \(\Theta(log_{k}n)\)

- \(n log_{k} n\) : \(\Theta(n log_{k} n)\)

- Quadratic: \(\Theta(n^{2})\)

- Cubic: \(\Theta(n^{3})\)

- Polynomial: \(\Theta(n^{k})\)

- Exponential: \(\Theta(k^{n})\)

- Factorial: \(\Theta(n!)\)

Divide-and-conquer recurrences

TODO

The “Guess-and-Confirm” Method

TODO

The “Master-Theorem” Method

TODO

Probabilistic Analysis and Randomized Algorithms

TODO

Amortized Analysis

TODO